When people hear the word mindfulness, sometimes they think of meditation or great mystical experiences. However, the concept of mindfulness is actually quite simple and ordinary. In this blog, I would like to demystify the concept of mindfulness. I want to make sure you understand that mindfulness is a concept that is readily accessible to everyone. While mindfulness does require patience and practice (just like anything good in life), it does not require decades of discipleship under a famous guru.

Perhaps you have heard the term “mindful.” “Mindfulness” seems to be the latest buzzword in treatment circles, not to mention society in general. But actually, the concept of mindfulness has been around for thousands of years. What does the term mindfulness mean? And what does it mean to be mindful?

DEAR Adult: One Path to Interpersonal Effectiveness (Part 9 of 10)

Whereas all the other skills mentioned so far are about self-regulation, interpersonal effectiveness inherently involves both the self and someone else. Therefore, interpersonal effectiveness inherently subsumes the other skill sets. After all, you can’t possibly deal with another person if you can’t even deal with yourself yet.

Working the TOM: One Path to Dialectical Thinking (Part 8 of 10)

Dialectical thinking is all about letting go of the extremes, learning to think more in the middle, learning to be more flexible with your cognitions, learning to see things from someone else’s perspective, learning to see things from multiple perspectives in your own head, and learning to update your beliefs when presented with new information.

TIP the Balance: One Path to Distress Tolerance (Part 6 of 10)

DBT distress tolerance is all about learning to cope in the moment without making it worse. It is about replacing impulsive, addictive, risky or self-injurious behaviors (in other words, any behavior that leads to even more of a crisis orientation) with more-effective coping strategies.

The RAIN Dance: One Path to Mindfulness (Part 5 of 10)

Mindfulness, by definition, is always a combination of both awareness and acceptance. The RAIN dance helps clients increase both awareness and acceptance of intense emotions and other triggers in a highly practical and applied manner. RAIN stands for Recognize, Allow, Inquire and Nurture.

Trauma stabilization through polyvagal theory and DBT

From article published by the American Counseling Association on September 14, 2021

By Kirby Reutter

Introduction (Part 1 of 10)

From my perspective, polyvagal theory has thus far provided us with the best working model of how trauma affects the brain and the body.

In the blog post on Restoring Balance with Relationships, do you remember how we learned the DEAR Adult tool to assert, appreciate, and apologize? In this post, you are going to learn a similar tool to continue your healing journey: DEAR Self. In particular, you will be writing a series of letters to your traumatized Self.

Please note: The following exercises should only be completed (1) if you are currently receiving support from a professional counselor, and (2) if you have already worked your way through the rest of the workbook.

Think of one of your traumatic experiences. If this is your first time doing this, do not select the worst trauma that ever happened to you. Instead, chose one to practice with that is not so triggering that it will cause you to relapse in your treatment. The format you will be using to write this letter is DEAR Self.

1. Describe

Recall that the first part of this sequence stands for describe. In the first part of your DEAR Self letter, you will describe a traumatic event that happened to you. You will describe the specific order of events. You will also describe what you experienced with each of your five senses (as many as apply): What you saw, what you heard, what you smelled, what you tasted, and what you felt.

2. Express / Empathize

Remember that the second part of this sequence stands for either express or empathize. Both apply in the DEAR Self letter. Express all the emotions that you felt when the trauma happened, as well as the emotions you experienced after the trauma ended. If necessary, identify the emotions that became frozen, numb, or stuck as a result of the trauma. Since you are writing this letter to the traumatized Self, provide the empathy that you never received at the time.

3. Assert - Appreciate - Apologize

Recall that the third part of this sequence stands for either assert, appreciate, or apologize. In your DEAR Self letter, you will be doing a little of each. First, you will assert to your traumatized Self that what happened was wrong and was not your fault, no matter what someone has told you. You may need to identify an ANT’s that you still believe about the trauma, and the dispute those ANT’s with balanced thinking. Second, you will verbalize appreciation to your traumatized Self for how strong and brave you were to have survived this trauma. Be sure to elaborate all of your positive qualities that allowed you to survive the trauma. Third, you will write the apology that you never received, or that you wish you could have received. You are not apologizing for your own trauma. Rather, you are apologizing that the trauma happened in the first place.

4. Reinforce

Remember that the fourth part of this sequence stands for reinforce. You may recall that reinforce means to either strengthen something or increase a behavior. In this case, you are going to strengthen your relationship to yourself as well as increase your dedication to the healing process. In other words, you are going to remind, reassure, recall, recommit. You will remind yourself that the trauma is now over. You will reassure yourself that you are now safe. You will recall all the skills you have learned along the way. And you will recommit to practicing these skills for as long as it takes. Another way to reinforce your healing journey is to find purpose in suffering. Ask yourself: How can my trauma be redeemed or repurposed for something positive? Or to help others? What insights about myself or life have I learned from this trauma that I could not have learned otherwise?

5. Self

Do you recall from the chapter on relationships how important your delivery is? Well I can’t think of any other letter in which your delivery will be more important! Remember that you are writing each part of this letter to your traumatized Self. Therefore, remember to be kind, gentle, and compassionate, the same way you would write to your best friend. In addition, remember to use all of the skills you have learned so in this book. It is especially important to remember to be accepting and non-judgmental.

If at any point writing this letter becomes too triggering, stop this exercise and take care of yourself by using your skills!

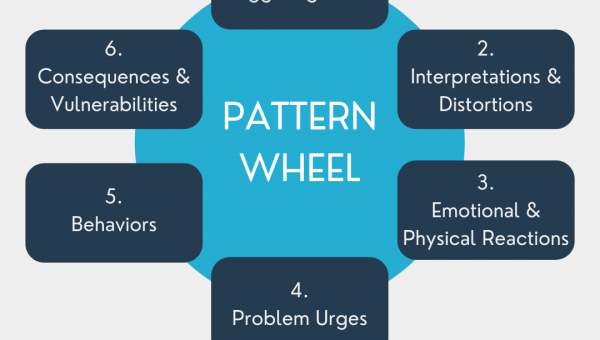

The Diary Card is a great tool to help you remember your skills as well as a great tracking device to help you monitor your daily ups and downs. But what happens when you’re really stuck? What do you do when you find yourself in the same situation over and over again? Or when you keep making the same mistakes time and time again? What happens when you are stuck in a blind spot, and you can’t see your way out? Now it’s time for the Pattern Wheel!

An example of a Pattern Wheel is provided below. Feel free to take a sneak peek now. Here are the steps to follow:

1. Identify a problem situation that keeps happening over and over again. This is called the prompting event.

2. What is your interpretation of this situation? Identify any ANT’s which may be influencing your interpretation.

3. What are your physical and/or emotional reactions to this situation?

4. What are your problem urges? Remember, problem urges are what you feel like doing when triggered, not necessarily what you end up doing.

5. Now identify your actual behaviors. What is your reaction to this situation?

6. What are the consequences of your behaviors? How do these consequences make you vulnerable (set you up) for the same old prompting event to happen all over again?

7. Once you have documented steps 1 through 6, go back to each step and identify at least one DBT skill that you have learned in this workbook that you can apply to stop this cycle from repeating itself.

There are several things I want you to notice about this exercise. First, did you notice that the Pattern Wheel is designed to increase awareness, just like the Diary Card? While the Diary Card is designed to increase general daily awareness, the Pattern Wheel is designed in increase awareness of specific dysfunctional cycles that you get trapped in. In particular, the Pattern Wheel helps you identify each link in that cycle so that you can develop better insight into what specifically is keeping you stuck. Second, did you notice that you can break this cycle at any point? There are specific DBT skills that you can use at each link in this chain which will cause the chain to break. Even though it’s always best to break the cycle as soon as possible, it’s never too late. You can still break the cycle even when after the behavior has already occurred, and now you need to do repair work. And you can even break the cycle after you have already blown right past the prompting event all over again…for the 100th time!

Let’s take a look at an example of the Pattern Wheel before you try this on your own. For the sake of argument, let’s just pretend that this is not a personal (recurring) example from my own marriage!

1. Prompting Event:

- My wife makes a suggestion, perhaps in the form of a critique.

Possible Skills:

- Mindfulness (Awareness + Acceptance)

2. Interpretation:

- “Nothing I ever do is ever good enough for her.”

- Possible ANT’s: over-generalizing, personalizing, mind-reading

Possible Skills:

- Work the TOM

- Play the DS

3. Emotional / Physical Reactions:

- I feel criticized.

- I feel humiliated.

- Breathing increases.

- Fists start to clench.

Possible Skills:

- Controlled breathing

- Muscle relaxation

4. Problem Urges:

- I feel like criticizing her back.

Possible Skills:

- Acting Opposite

- Letting Go

5. Actual Behavior:

- I say something negative to her.

Possible Skills:

- LUV Talk

- Get in my CAR

6. Consequences / Vulnerabilities:

- The negative comment I make about my wife confirms her original criticism. Because of how I handled this situation, I have directly contributed towards the same prompting event that started the whole sequence in the first place.

Possible DBT Intervention:

- DEAR Adult – Appreciate

- DEAR Adult – Assert

- DEAR Adult – Apologize

Enough about my own dysfunction. Now it’s your turn to practice!